We all hear about SOLID principles, but what does SOLID actually mean in the trenches of real-life iOS app development? Why should these five letters matter to you? If you’ve ever found yourself pondering these questions, you’re in the right place. SOLID isn’t just academic jargon; it’s a blueprint for building software that’s as resilient and adaptable as it is elegant. Let’s unpack SOLID principles piece by piece, showing you how they apply in your day-to-day iOS development work. Here’s the rundown on why SOLID could be the game-changer you’ve been looking for:

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP):

Clarified Definition: Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) mandates that every module, class, or function should have one, and only one, reason to change.

This principle underpins the design where each component is tasked with a single responsibility, promoting clarity, coherence, and ease of maintenance.

Practical Example: Application Structure

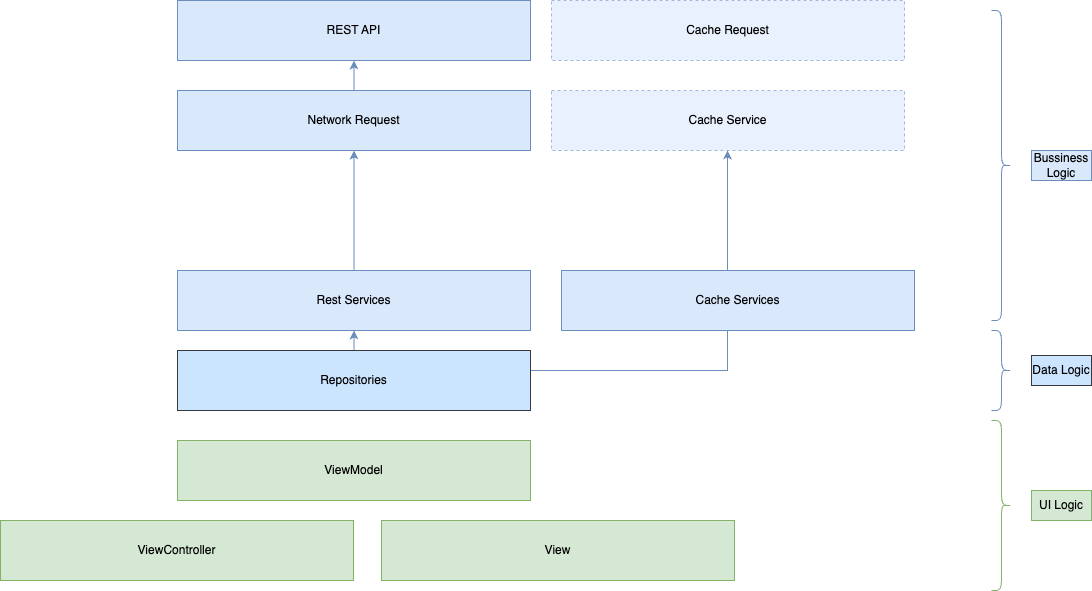

- Business Logic Layer: This layer is pivotal for managing data transfers, encompassing operations through REST APIs or cache requests. Its sole responsibility is to ensure that data is correctly fetched, processed, and made available to other parts of the application. By isolating the business logic, the app can adapt to changes in business rules without affecting other system parts.

- Data Logic Layer:

Service Components: Including Rest Service and CacheService, these components are dedicated to handling specific types of data operations — fetching data from a server or managing local cache, respectively.

Repositories: Act as intermediaries between the service components and the business logic layer. Repositories consolidate data sources, making it simpler for the business logic to request and receive data without concerning itself with the origin (REST API or cache). This setup aligns with SRP by segregating data fetching mechanisms from data processing and usage logic. - UI Logic Layer:

ViewController/SwiftUI View: Responsible for presenting data on the screen and handling user interactions. This layer focuses solely on UI-related tasks, ensuring a clear separation from data handling and business logic.

ViewModel: Serves as the bridge between the UI logic and business logic, preparing data for display and reacting to user inputs. The ViewModel transforms data from the business logic layer into a form that’s easy to present in the UI, adhering to SRP by isolating presentation logic from data processing and business rules.

Why This Matters?

The segregation into Business Logic, Data Logic, and UI Logic layers exemplifies SRP in action. By structuring an iOS app into these distinct layers, each with a focused responsibility, developers can achieve a modular design that simplifies understanding, enhances maintainability, and facilitates scalability. Changes in one layer, such as modifying data sources in the Data Logic layer or updating UI components, have minimal impact on others, demonstrating the flexibility and resilience of adhering to SRP.

Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

Definition: The Open/Closed Principle (OCP) stipulates that software entities (such as classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This principle advocates for designing your software in such a way that new functionality can be added with minimal changes to the existing code. It encourages the use of interfaces or abstract classes to allow behaviors to be extended without altering the code that uses those behaviors.

Practical Example:

Consider an iOS application that displays various types of content, such as articles, videos, and podcasts, each requiring a different presentation style in a list. Initially, you might have a single ContentViewController handling all content types, leading to multiple if-else statements or switch cases to render each type. This design violates OCP because adding a new content type requires modifying the ContentViewController‘s code.

Solution:

Define a Content Protocol: Start by defining a protocol (or abstract base class in other programming paradigms) that represents the general behavior of content that can be displayed.

protocol DisplayableContent {

var title: String { get }

func displayContent() -> UIViewController

}

Implement Content Types: For each content type (articles, videos, podcasts), create a class that conforms to DisplayableContent, implementing the displayContent method to return the appropriate view controller for displaying that content type.

class ArticleContent: DisplayableContent {

var title: String

// Article specific properties

init(title: String) {

self.title = title

}

func displayContent() -> UIViewController {

// Return ArticleViewController configured with the article content

}

}

class VideoContent: DisplayableContent {

var title: String

// Video specific properties

init(title: String) {

self.title = title

}

func displayContent() -> UIViewController {

// Return VideoViewController configured with the video content

}

}

Displaying Content: The ContentViewController can now iterate over a collection of DisplayableContent items, calling displayContent on each to obtain the appropriate view controller for display, without needing to know the specifics of each content type.

class ContentViewController: UIViewController {

var contents: [DisplayableContent] = []

func displayContents() {

contents.forEach { content in

let viewController = content.displayContent()

// Display the viewController

}

}

}

Why This Matters?

By adhering to OCP, the iOS app becomes more flexible and easier to extend. Adding a new content type, such as a podcast, simply involves creating a new class that conforms to DisplayableContent without modifying any existing ContentViewController code. This approach significantly reduces the risk of introducing bugs into existing functionality when extending the application’s capabilities.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Definition: The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) asserts that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without altering the correctness of the program. In simpler terms, if class A is a subtype of class B, then we should be able to replace B with A without disrupting the behavior of our program.

This principle encourages design that promotes reusability and correct inheritance hierarchies, ensuring that derived classes extend base classes without changing their behavior.

Practical Example:

Consider an iOS app with a feature to display different types of content, each requiring a different kind of view to render. You might start with a base class ContentView and subclass it to create specific content views like ArticleView and ImageView.

Violation Scenario:

class ContentView {

func display() {

print("Displaying content")

}

}

class ArticleView: ContentView {

override func display() {

print("Displaying article")

}

}

class ImageView: ContentView {

override func display() {

print("Displaying image")

}

}

class VideoView: ContentView {

override func display() {

fatalError("Video cannot be displayed with this method")

}

}

In this scenario, replacing ContentView with VideoView in the program could lead to runtime errors, as VideoView cannot be used interchangeably with its siblings without altering the program’s behavior, violating LSP.

Adherence Solution:

To adhere to LSP, ensure that all subclasses of ContentView can indeed replace ContentView without issue. For the VideoView case, it’s clear that a different approach is needed, as videos might require additional operations like play, pause, and stop.

protocol Displayable {

func display()

}

class ArticleView: Displayable {

func display() {

print("Displaying article")

}

}

class ImageView: Displayable {

func display() {

print("Displaying image")

}

}

protocol Playable {

func play()

func pause()

func stop()

}

class VideoView: Playable {

func play() {

print("Playing video")

}

func pause() {

print("Pausing video")

}

func stop() {

print("Stopping video")

}

}

By introducing protocols Displayable and Playable, we segregate the functionalities appropriately, ensuring that our program can use ArticleView and ImageView interchangeably for displaying content, while VideoView is used in contexts requiring playback control. This design adheres to LSP by maintaining behavioral consistency across subclasses and protocols, enhancing the robustness and flexibility of the app’s architecture.

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Definition: The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) advocates that no client should be forced to depend on interfaces it does not use. This principle encourages splitting large, monolithic interfaces into smaller, more specific ones so that clients only need to know about the methods that are of interest to them.

It aims to reduce the side effects of changes in code and improve system flexibility by minimizing unwanted dependencies.

Practical Example:

In the development of an iOS app, consider a module for handling user profiles, which includes displaying profile information, editing profile details, and managing user settings. Implementing a single interface (or protocol in Swift) for all these functionalities would force any class implementing this interface to provide implementations for all methods, even if they’re not relevant.

Violation Scenario:

protocol UserProfile {

func displayProfile()

func editProfile()

func changeSettings()

}

class UserProfileView: UserProfile {

func displayProfile() {

// Implementation for displaying user profile

}

func editProfile() {

// Implementation for editing profile

}

func changeSettings() {

// This functionality is not relevant to a view component

}

}

In this scenario, UserProfileView is forced to implement changeSettings(), a method it does not need, violating ISP.

Adherence Solution:

To adhere to ISP, the large UserProfile protocol should be segregated into smaller, more specific protocols:

protocol ProfileDisplayable {

func displayProfile()

}

protocol ProfileEditable {

func editProfile()

}

protocol SettingsManageable {

func changeSettings()

}

class UserProfileView: ProfileDisplayable {

func displayProfile() {

// Implementation for displaying user profile

}

}

class UserProfileEditor: ProfileEditable, SettingsManageable {

func editProfile() {

// Implementation for editing profile

}

func changeSettings() {

// Implementation for changing settings

}

}

By segregating the UserProfile protocol into ProfileDisplayable, ProfileEditable, and SettingsManageable, each class can implement only the interfaces relevant to its functionality. This design adheres to ISP by ensuring that UserProfileView is not burdened with unrelated methods, thus enhancing modularity and reducing the impact of changes.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Definition: The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) states that high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules, but both should depend on abstractions. Furthermore, these abstractions should not depend upon details; rather, details should depend upon abstractions.

DIP aims to decouple software modules, making high-level modules independent from the concrete implementations of their dependencies, thereby enhancing modularity, ease of testing, and flexibility in code.

Practical Example:

Consider an iOS app that fetches and displays news articles. The high-level module (e.g., a view controller) should not directly depend on a low-level module (e.g., a network service for fetching news) for retrieving the articles. Instead, both should rely on an abstraction.

Violation Scenario:

class NewsNetworkService {

func fetchNews() -> [Article] {

// Fetch news from the network

}

}

class NewsViewController {

var newsService = NewsNetworkService()

func updateUI() {

let articles = newsService.fetchNews()

// Update the UI with articles

}

}

In this scenario, NewsViewController directly depends on NewsNetworkService, making it hard to test NewsViewController without also involving NewsNetworkService, and difficult to switch to a different mechanism for fetching news in the future.

Adherence Solution:

To adhere to DIP, introduce an abstraction (a protocol in Swift) that represents the action of fetching news, and make both the high-level and low-level modules depend on this abstraction.

protocol NewsFetching {

func fetchNews() -> [Article]

}

class NewsNetworkService: NewsFetching {

func fetchNews() -> [Article] {

// Fetch news from the network

}

}

class NewsViewController {

var newsService: NewsFetching

init(newsService: NewsFetching) {

self.newsService = newsService

}

func updateUI() {

let articles = newsService.fetchNews()

// Update the UI with articles

}

}

With this approach, NewsViewController now depends on the NewsFetching protocol rather than a concrete NewsNetworkService class. This decoupling allows for easy substitution of the news fetching mechanism (for example, using a local cache or a different API) without changing NewsViewController‘s code. It also facilitates unit testing by allowing you to provide a mock or stub implementation of NewsFetching.

So, we’ve demystified SOLID principles and showcased their power in the context of iOS app development. It’s clear that SOLID isn’t just a set of guidelines; it’s a mindset that can transform the way you approach coding. By embracing the principles of Single Responsibility, Open/Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion, you’re not just improving your code; you’re setting a new standard for excellence in your projects.

Adopting SOLID principles might require a shift in how you think about coding, but the benefits — more maintainable, scalable, and robust apps — are undeniable. This guide is your stepping stone to integrating these principles into your development process. As you do, you’ll find your software becoming more solid with every line of code. Let’s make coding not just a task, but a craft. Ready to take your iOS apps to the next level?

Leave a comment